Issue 50, Spring 2019

It seems scarcely possible, but it is ten years since we first opened our Highland Hotel in Fort William.

It was the culmination of an ambition that started in 2001. Twice we had made unsuccessful offers to purchase this historic hotel, which we knew would be a perfect addition for Lochs and Glens as it would enable us to offer a whole new range of day excursions. Then, in 2006 the company operating the hotel went into liquidation and, at last, we were able to acquire the property at a sensible price.

It was the first new addition to our group since I retired in 2000 so it was my son Neil who supervised the renovations that were needed to bring the property to a Lochs and Glens standard. It would prove to be a demanding undertaking as the interior was stripped back to the stone in many places to eliminate all traces of wood rot, the scourge of West of Scotland buildings. But perhaps the greatest challenge was balancing the need to preserve the fine Victorian craftsmanship, which is such a feature of this Grade II listed building, whilst at the same time, opening up the public areas to give a feeling of light and spaciousness. To Neil’s great credit this was beautifully achieved and the hotel opened on schedule and importantly, within the overall £7m budget.

Another anniversary, the modest birth of Lochs and Glens Hotels will fall next April. It will then be 40 years since we made the momentous decision to sell our family home and, together with loans from family, bank and brewery, use the proceeds to buy a dilapidated loch-side hotel for the princely sum of £70,000. I would like to be able to say it was part of a grand plan, but in reality for the first few fraught years the only aim was to avoid bankruptcy!

And finally, one more anniversary to mention, and I hope our readers will forgive the indulgence as it is on a more personal level, and that was my most enjoyable 80th birthday surrounded by the entire family at Walton Castle in Somerset last summer unforgettable occasion.

Michael Wells OBE, Chairman

Lochs and Glens Hotel in Wartime

The two ‘Great Wars’ of the 20th century had a profound effect on several of our hotels, either as a result of being requisitioned by the government or being put to a different use or, as in one case, of being bombed.

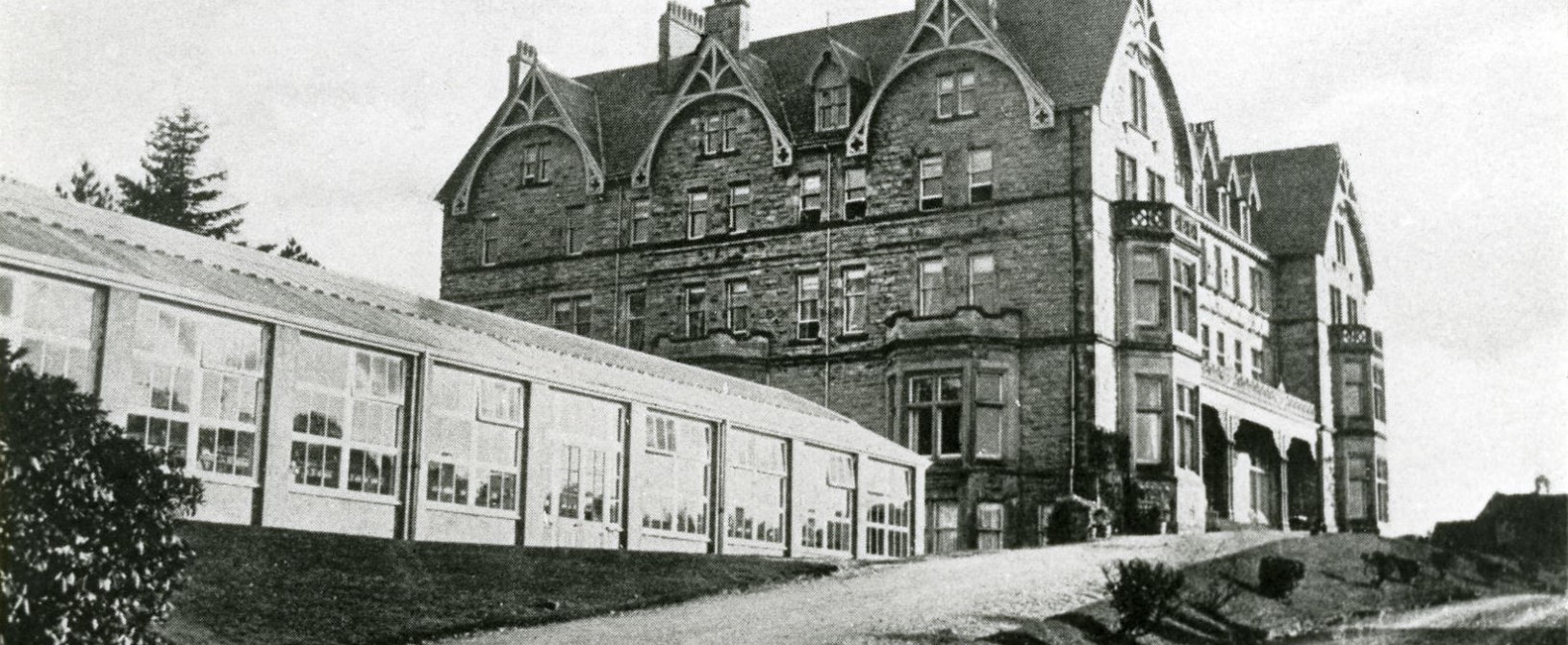

At the time of the outbreak of the first World War, the Highland Hotel in Fort William was leased to the London Polytechnic and was used as a base for student educational study tours. This arrangement became unviable as the war persisted and eventually the hotel was forced to close and the lease lapsed. A government inspired initiative designed to help severely disabled servicemen returning from the trenches led to the hotel being converted into the Oppenheimer Diamond Factory. The hotel tennis court (where the new wing now stands) was replaced by a glass pavilion and the ex-servicemen were given six months training in cutting and polishing industrial diamonds before getting guaranteed employment at a good wage. This arrangement continued until 1924 when Oppenheimer’s went into liquidation and the lease was returned to the London Polytechnic.

During the second World War, the Highland Hotel was requisitioned by the War Ministry and became the headquarters of HMS St. Christopher, a coastal forces training base that included most of the other hotels in Fort William. A variety of courses were run, many involving torpedo use along Loch Linnhe. It is estimated that 55,000 personnel of various nationalities passed through the base during its four years of operation.

The Loch Achray Hotel which had first opened in 1929 was also requisitioned during World War II but, for an entirely different purpose - food production. The field in front of the hotel where the highland cows and sheep now graze was, at one time, a nine hole golf course but, with the outbreak of hostilities, the fairways and greens were converted back to farmland where vegetables were cultivated to help feed the local population. The labour was provided by Italian and German prisoners of war until they were repatriated in 1946. The prisoners kept their wartime home looking as cheerful as possible by keeping the stone troughs around the hotel planted with flowers. It all seems a far cry from the usual grim portrayal of a prisoner of war life.

The Inversnaid Hotel remained open throughout the duration of both wars, although just who was staying there has never been clear. No visitor books survived from those periods, but George Buchan, from whom we purchased the hotel in 1984, had worked there throughout the second world war and, on more than one occasion, he shared his memories of that time - usually over a bottle of malt whisky! He particularly recalled the night of 5th May, 1940 when burning bracken at the rear of the hotel had, from high altitude, been mistaken for the burning Clydeside docks, 50 miles away. Twenty eight bombs were dropped in the immediate area and one unfortunately fell onto the hotel causing considerable damage. Throughout the raid the staff huddled under the staircase and fortunately remained uninjured. Repairs were made and the hotel reopened and during the next few years many mysterious groups of varying nationalities were booked into the hotel by the War Ministry, as George recounted - ‘all very hush hush’. Just what was discussed in the meeting room was never discovered, despite the best efforts of the curious staff.

The Loch Awe Hotel remained open throughout both world wars. Little is known of the guests during WW I, but the visitors book shows that during WW II, the clientele were mainly military; senior officers who needed a standard of accommodation befitting their rank. Nearly all of these officers were associated with HMS Quebec, the training centre which was located not far away on the shores of Loch Fyne. Its prime purpose was to train army and navy service personnel in the use of landing craft for landing assault troops, supplies and weaponry onto heavily defended enemy occupied beaches in preparation for the 1944 Normandy Invasion. Its contribution to the war effort cannot be overstated.

While the senior officers were enjoying the comforts of the Loch Awe Hotel, the other ranks were billeted in Nissen huts on the loch shore. Inverary was the nearest town for relaxation, but its charms were apparently not appreciated judging by this poem from the period written in typical army down-to-earth language.

Ode to Inveraray

This bloody place is a bloody cuss

No bloody tram, no bloody bus

And do they care for bloody us?

In bloody Inveraray

The bloody films are bloody old

The bloody seats are bloody sold

Can't get in for bloody gold

In bloody Inveraray

It bloody pours, it bloody rains

No bloody kerbs, no bloody drains

Ain't no-one got no brains

In bloody Inveraray

Everything's so bloody dear

A bloody bob for a bloody beer

And is it good? no bloody fear

In bloody Inveraray

All bloody work no bloody games

No bloody fun with bloody dames

Wouldn't even tell their names

In bloody Inveraray

Enough of this ere bloody rhyme

Everything's just a waste of time

Next week'll be just t’ sime

In bloody Inveraray.

The Glenfinnan Monument

Many of our regular guests will have noticed the imposing Glenfinnan Monument when travelling between Fort William and Mallaig. The may have noticed it from the Jacobite Steam Train as they crossed the famous viaduct, familiar to Harry Potter fans, and some may even have climbed the monument’s spiral stone stairs to admire the view down the length of Loch Shiel from the summit. Those familiar with this iconic Scottish landmark may not be aware of the reason it was built.

Constructed in 1815, it celebrates the moment when Bonny Prince Charles raised his standard on a nearby hill and announced to the assembled clans that he was claiming the British throne in the name of his father James Stuart. This signalled the start of the Jacobite Rising.

Constructed in 1815, it celebrates the moment when Bonny Prince Charles raised his standard on a nearby hill and announced to the assembled clans that he was claiming the British throne in the name of his father James Stuart. This signalled the start of the Jacobite Rising.

Initially, with considerable clan support from the highlands and north east, the assembled army made good progress having been assured that there would be additional help from both English and French Jacobites as they made their way south towards London. Eventually they arrived in Derby, but the anticipated support never materialised and, with the news that the English government was mobilising a response, it was decided that they must retreat. Despite the Duke of Cumberland advancing from London with an army of 12,000 and General Wade marching south from Newcastle with his troops, the Jacobites managed to make their way back to Scotland, but they continued to be pursued until the final confrontation near Inverness at the notorious Battle of Culloden on 16 April 1746. The English army led by the Duke of Cumberland were merciless in their determination to end Jacobitism once and for all. 2,000 Jacobites were killed or wounded with such brutality that henceforth Cumberland became known as ‘Butcher Cumberland’.

Bonny Prince Charles however, managed to escape and, despite the vast reward of £30,000 placed on his head, he avoided capture. Five months later he was picked up by a French frigate not far from Glenfinnan, never to return. He died in Rome in 1788.

By 1815, when the Jacobite cause was no longer a political threat, Alexander Macdonald of Glenaladale built the memorial tower at Glenfinnan to commemorate the raising of the standard of the Young Pretender. The statue of an anonymous highlander was added in 1835.

Inveraray

Having reproduced the scurrilous wartime description of Inveraray, I feel I must redress the balance by saying that there have certainly been some changes since the troops were looking for their entertainment in the town. There is definitely no shortage of kerbs and drains now and there can be no complaints about the quality of the films as there is no longer a cinema. The weather is probably much the same but I am sure the beer is much improved. However, whether or not the dames are more or less likely to give there names, I wouldn’t know.

But I do know that a visit to this charming Georgian town has, over the years, been a consistently popular destination with our guests.